by Shivanee Ramlochan, Paper Based Blogger

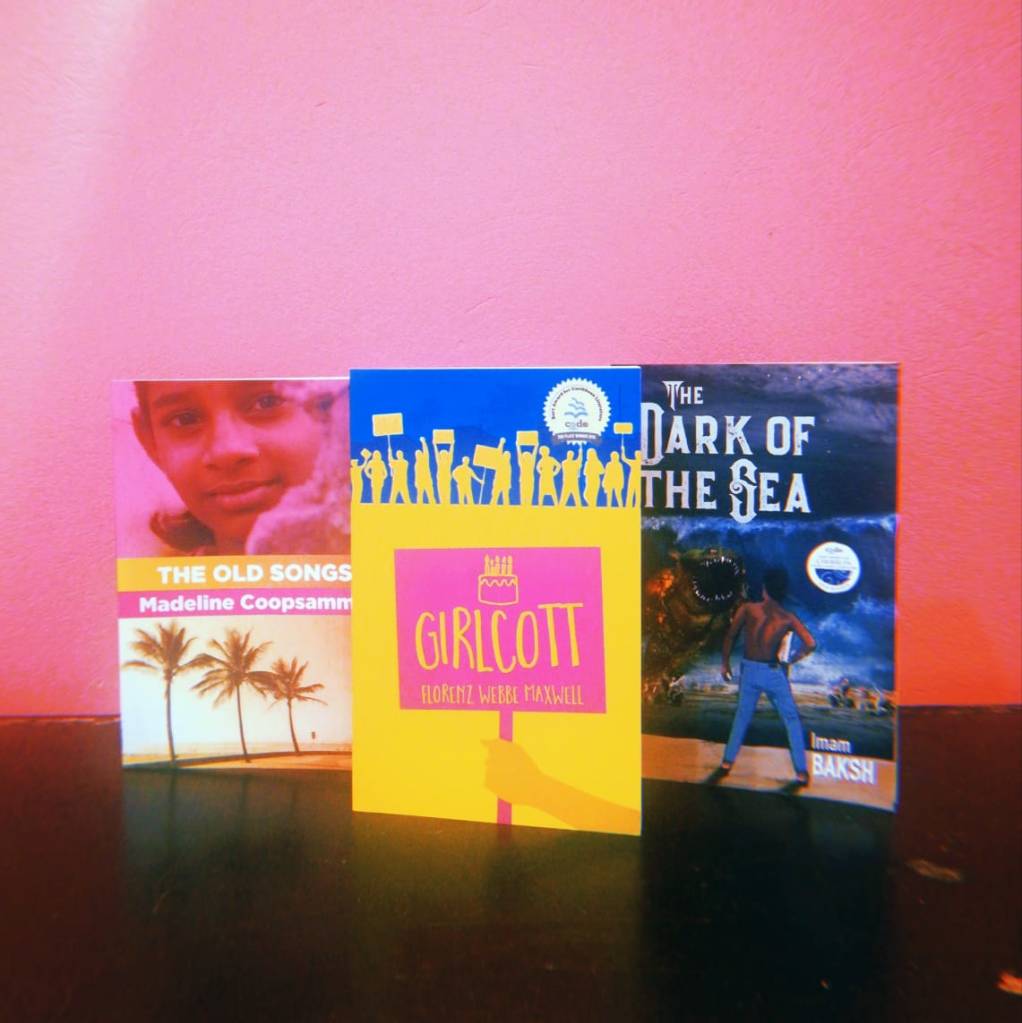

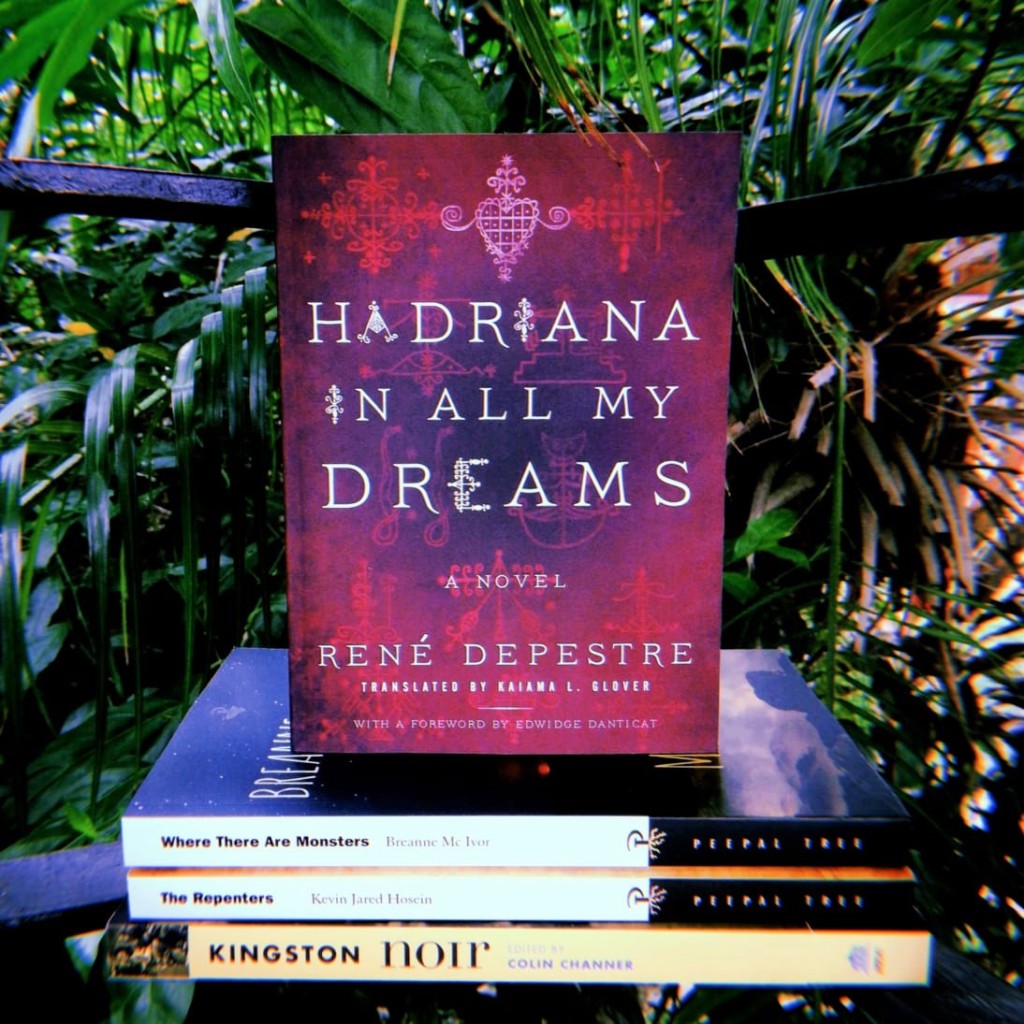

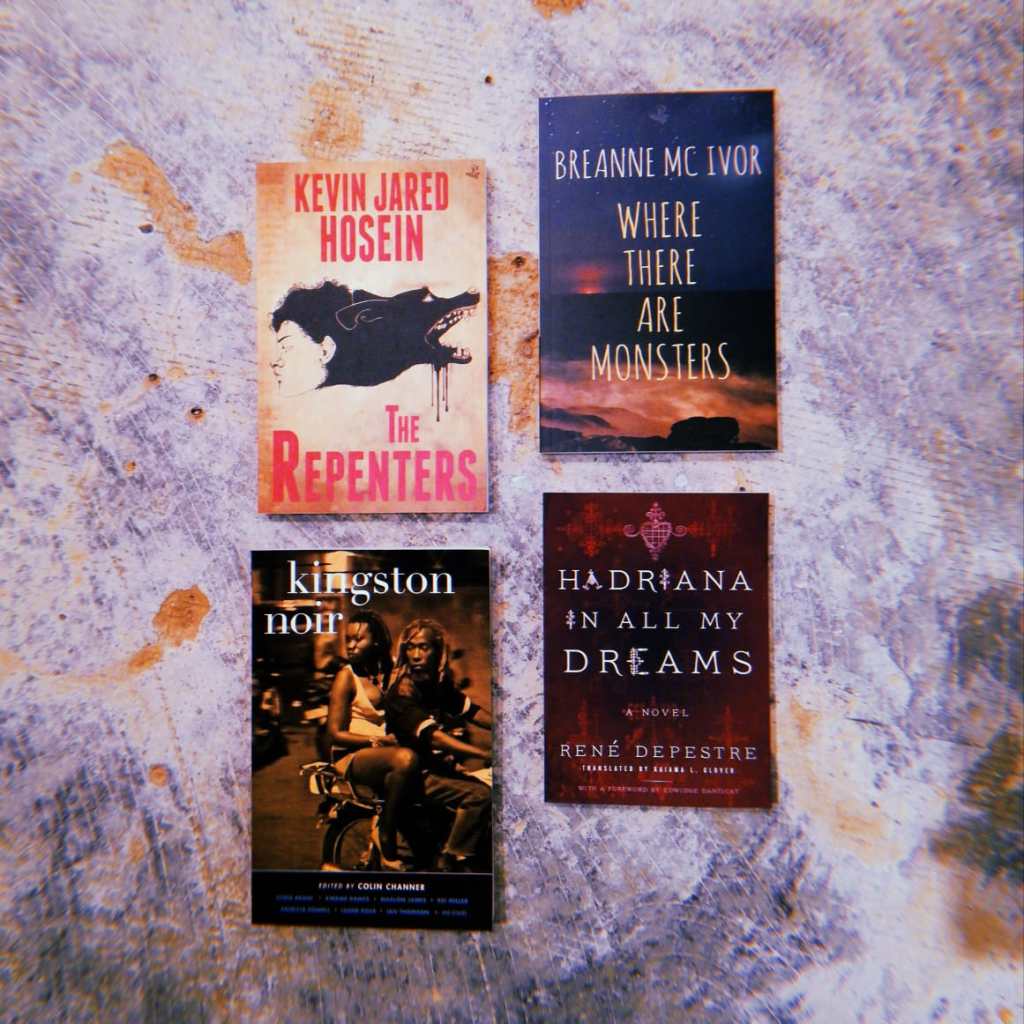

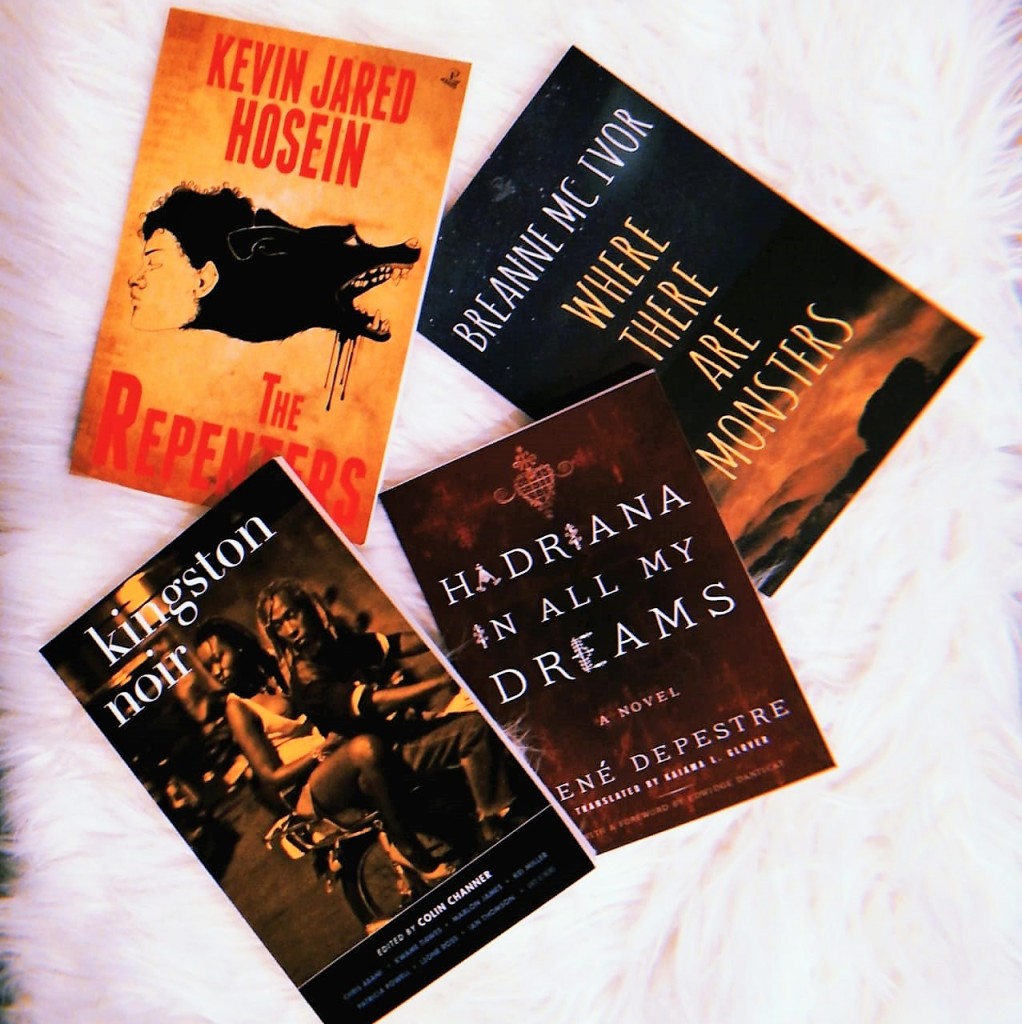

Images by Alicia Viarruel

Here at Paper Based Bookshop, we celebrate books, reading and the lit-community every day, especially for all things Caribbean. It’s thrilling to take part in UNESCO’s World Book and Copyright Day, dedicated to improving global access to books in spaces that most need it. Here are five titles from our shelves to yours, each of them inspiring reading, discovery, and the power of imagination.

What would you do to protect your children, and what would you sacrifice to keep one of them safer than the other? By equal turns disturbing and atmospheric, Golden Child asks difficult questions from its earliest pages that have nebulous answers, leaving the reader to perform acts of moral and emotional empathy on its subtly, sharply written prose. Adam’s strength in navigating the rural Trinidadian landscape is a quietly impressive force, giving us darkly lit gravel roads, whispering trees that hint of menace, and the ever-present call of a threatening Caribbean sea. Read it, and be ready to feel haunted.

“Botany”

Plant these seeds so you can tend a forest

so you can long for a stranger to feed the wild birds.

The poems of Nicholas Laughlin might be called strange, but they might also be known as mysteries. If that sounds like a contradiction, we urge you to spend time with Laughlin’s debut collection, which alchemizes, transmutes, and reports on the incredible weirdness of our (in)human conditions. Particularly in a world experiencing severely restricted movement, these are words you can travel to, from jungles to tundras, mountain peaks to the unknowable hearts of so many places we call home.

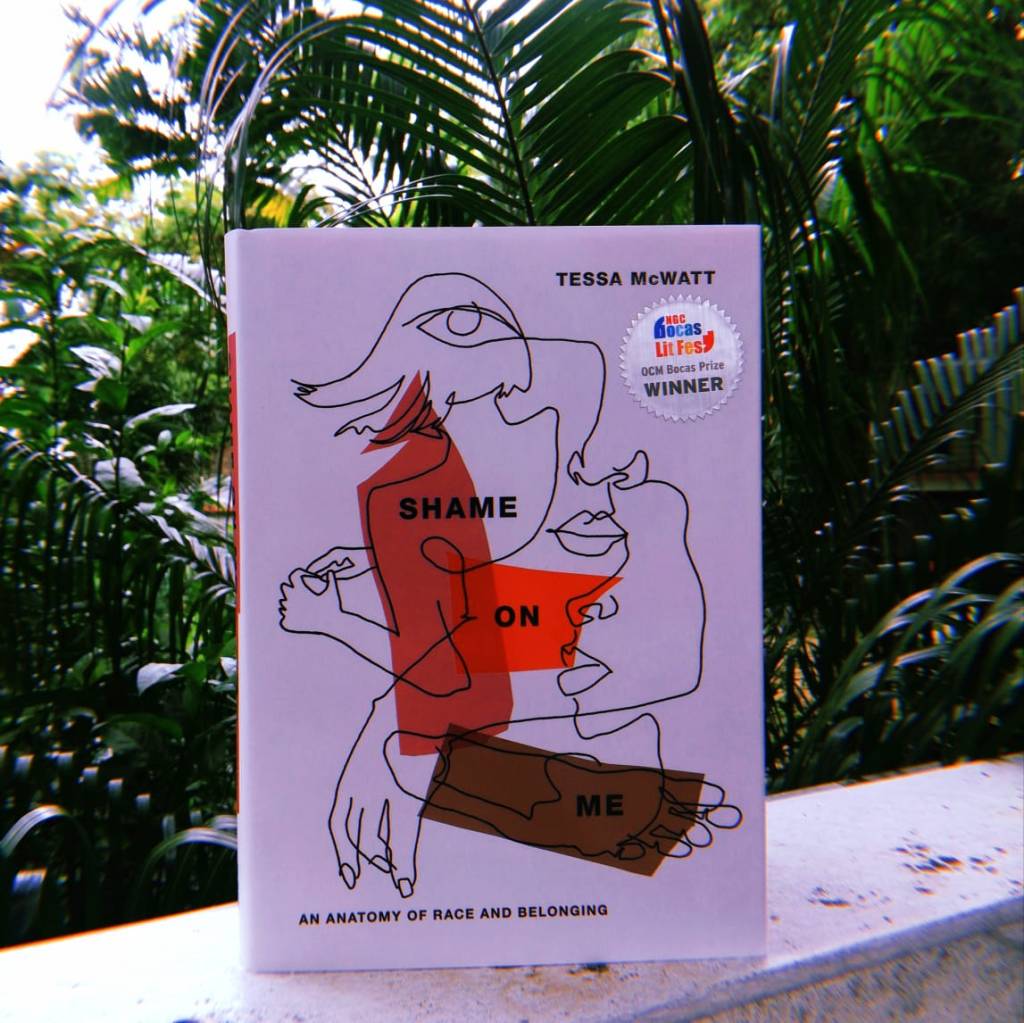

Drawing on the facts, frustrations and triumphs of her own body, Tessa McWatt’s winner of the 2020 OCM Bocas Prize for Non-Fiction Caribbean Literature is a powerful companion to anyone, Caribbean or not, who’s felt othered in their physical selves. Shame on Me is sequenced and formatted in chapters dedicated to body parts: in each one, the author allows the voice of her childhood and adult selves to mingle with copious research, medical anatomy illustrations, and popular science. The results are deeply moving, showing how postcolonial bodies are ravaged by racism and xenophobia, showing how they can fight back, resoundingly.

Here is coming of age fiction in linked short stories like you’ve imagined in your heart of hearts: unapologetically spilling secrets, revealing the thick, complex braid of love and trouble between mother and daughter, in a world where home-cooked food conjures love, and girls rebel against the rigid matriarchies ruling their thoughts and deeds. Kara Davis, our narrator, isn’t interested in being a superheroine or a badass; she wants to belong and be herself, a two-pronged ask that brings intergenerational conflicts roaring to life. Through each story, Reid-Benta envelops her reader in skilful narrative control, making each description vivid, sustaining.

The entire world — the Caribbean no exception — watched Amanda Gorman make history on live television. In a backdrop of so much uncertainty, against the soundtrack of a past year studded with turmoil, The Hill We Climb became more than a single poem for a presidential inauguration: it captured and held hearts that had been badly bruised, over and over. Offering hard-won hope, and wisdom distilled into brief, intense lines that linger long after a first reading, Gorman says it best herself:

Let the globe, if nothing else, say this is true,

that even as we grieved, we grew

Happy World Book and Copyright Day 2021, everyone!